|

EYRE'S

JOURNEY ACROSS THE GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT

Eyre's truly remarkable crossing of The Great Australian Bight and

the Nullarbor Plain is the feat for which he is best remembered. In

the full heat of summer and the depths of an Australian winter (1840-41),

Edward John Eyre explored the rugged and unforgiving coastline between

Streaky Bay on South Australia's west coast, and King George's Sound

- present day Albany - in Western Australia. In all a distance of

over 1200 miles.

An Auspicious Beginning

Eyre's

westward journey accross the Australian continent began at Streaky

Bay on 3 November 1841. With support and supplies from the sailing

cutter "Waterwitch", Eyre and his men literally hacked their way through

dense Mallee scrubland, heaving their axes from five in the morning

until ten at night.

Within three days Eyre's expedition had met

with a friendly group of aboriginal people at Smoky Bay. Led by an

amiable old man named Wilguldy, Eyre's expedition was blessed in being

able to rely on local aboriginal knowledge when digging for water

in sandhills. Eyre was particularly impressed with the ease with which

Wilguldy's people could live off the land, gathering food sources

such as snakes, lizards, goannas, bandicoots, wallabies and a variety

of native fruits.

|

Pig Face plants and their

edible fruits

|

|

Ably led by Wilguldy, Eyre's

expedition made good progress and halted at Denial Bay where supplies

were offloaded from the cutter "Waterwitch' Throughout the journey,

Wilguldy's assistance was much appreciated and Eyre often rewarded

Wilguldy with the privilege of riding on horseback - an event that

never failed to impress Wilguldy's tribesmen!

By 17 November 1840 Eyre's expedition had

reached Fowlers Bay - the next staging point in their crossing of

the Nullarbor Plain and the Great Australian Bight. Fowlers Bay again

saw the good ship "Waterwitch" replenish Eyre's expedition with supplies.

Eyre Discovers Water At Yeer Kumban Kauwe

During the next two months Eyre made three

attempts to round the Head of Bight. Water was always in critically

short supply - particularly so on his second failed attempt when Eyre

was clearly distressed to lose three of his best draught horses to

exhaustion, thirst and the blistering Australian summer sun. After

the second failed attempt to reach the Head of Bight Eyre realised

that travelling with drays was impossible in such desolate country.

There were just too many sandhills, and where there weren't sandhills,

the scrub was too thick to make for rapid travelling.

On his third attempt Eyre wisely resorted

to a packhorse and finally reached the Head of Bight on 7 January

1841. Whilst camped at the Head of Bight friendly aborigines again

showed Eyre a number of native waterholes located in a vast system

of huge white sandhills. In Eyre's own words "... we were indebted

solely to the good nature and kindness of these children of the wilds

for watering our horses: unsolicited they offered us aid, without

which we never could have accomplished our purpose."

In the local aboriginal language these

waterholes were called Yeer Kumban Kauwe. Today, 160 years later,

these amazingly beautiful sandhills can still be seen from the vantage

point of the whale watching platform at the Head of Bight; and although

the sandhills may have drifted, there's no doubt fresh water can still

be found there.

To the west of Yeer Kumban Kauwe Eyre could

see the enormous cliffs of the Great Australian Bight. Today we know

them as the Bunda Cliffs. Eyre resolved to explore the area in the

hope of pioneering an overland stock route to Western Australia. Eyre

made a round trip along the cliffs for a distance of forty five miles.

On 11 January Eyre headed back to his support depot in Fowlers Bay

- a distance of 130 miles or more by horse.

Fireworks At Fowler's Bay and Unexpected Delays

Eyre and his party camped at their Fowlers

Bay depot until the last week of February and on the evening of the

23rd Eyre treated Fowlers Bay to its very first fireworks display!

As Eyre himself wrote "... on the afternoon of the 24th I intended

finally to evacuate the depot, to amuse my natives, I had all the

rockets and blue lights we had fired off."

The departure of Eyre's expedition was

delayed a day however, with the unexpected arrival of the cutter "Hero".

On board the "Hero" was Mr. Germain, a friend who earnestly advised

Eyre against crossing the Great Australian Bight. Eyre also received

letters from Governor Gawler and colonists in Adelaide begging him

not to undertake such a perilous expedition - especially given that

Eyre would be unable to rely on ship supplies farther west than Fowlers

Bay.

The next day, 25 February 1841, Eyre continued

his journey westwards to King George's Sound - still over 1000 miles

away. Accompanying Eyre was his trusted friend, John Baxter, and teenage

aboriginal boys Wylie, Joey and Yarry. Transport for the party consisted

of 9 horses, a Timor Pony and one foal. Food supplies were calculated

at an allowance of six pounds of flour per person per week - approximately

240 pounds of flour per person..

By 2 March Eyre's expedition had travelled

over 120 miles and finally reached the Yeer Kumban Kauwe sandhills

- a place where they knew water could be found by digging wells. Despite

the constant torment of sand, wind, and the painful stings of large

horse flies, Eyre rested for six days before pressing on to the west,

beyond the Bunda Cliffs of the Great Australian Bight. From the accounts

of the local Mirning people, Eyre knew that the next waterholes were

well over 120 miles away to the west, beyond the Bunda Cliffs of the

Great Australian Bight.

Eyre Crosses The Waterless Bunda Cliffs

On the 7th March Eyre's expedition again

headed west, travelling both by day and night through the Nullarbor

Desert. Travelling at a desperate pace of 25 miles per day both man

and beast endured great suffering. Eyre's exhaustion was evident as

he sometimes dozed off to sleep even as he walked. For 4 days Eyre's

expedition battled their way through salt bush and tea tree scrub,

trekking over the seemingly never ending limestone country to the

north of the Bunda Cliffs.

By March 10 Eyre had scouted ahead of

the main expedition party in the hope of discovering a break in the

Bunda Cliffs that lined their route, but none were to be seen. Eyre

was concerned for his pack horses which had been travelling for 4

days without any water whatsoever. The condition of Baxter and the

aboriginal boys was hardly any better - with all suffering parching

thirsts.

Despite the expeditions cruel lack of

water and the real prospect of death, remarkably Eyre still possessed

a romantic vision of the Australian wilderness. In his journal Eyre

was moved to write:

| "Distressing and fatal as

these cliffs might prove to us, there was a grandeur and sublimity

in their appearance that was most imposing, and which struck

me with admiration. Stretching out before us in unbroken line,

they presented the singular and romantic appearance of massy

battlements of masonry, supported by huge buttresses, and glittering

in the morning sun which had now risen upon them, and made the

scene beautiful even amidst the dangers and anxieties of our

situation." |

The Daunting Bunda Cliffs

A Brief Respite At Eucla

By

the morning of 11 March Eyre had passed the Bunda Cliffs. Eyre's

situation was still desperate however. During the previous night

Eyre had unwittingly trekked many miles past some sandhills - possibly

the very water bearing sandhills that the aborigines had mentioned

at Yeer Kumban Kauwe. Eyre took a desperate gamble and pressed on,

forlornly hoping to reach another set of sandhills he could see

in the distance. Today these sandhills can be found near the township

of Eucla, and they proved to be the expedition's salvation. Upon

turning into the sandhills Eyre was fortunate to strike the very

place where aborigines had dug little wells.

For a week Eyre and his expedition remained

at the Eucla sandhills. Much time was spent attending the horses,

and retrieving valuable stores that Baxter had been previously forced

to abandon many miles away to the east. The 18th March saw Eyre and

his party again heading west, but the horses were still in poor condition

and in need of water. Eyre ordered Baxter to drop the expedition's

stores and return to the Eucla sandhills, where the horses could rest

and later return with a good supply of water.

Difficulties With Making A Cup Of Tea on The Nullarbor

By March 26 Eyre's expedition was travelling

through dense scrub and over sandy ridges. Eyre realised that progress

was still unbearably slow and that the pack horses loads needed to

be lightened. Whilst the native boys were asleep, Baxter and Eyre

set about throwing away items that could be dispensed with. In all

a total of 200 pounds of items were discarded - including clothes,

buckets, water kegs, pack saddles, some firearms and a quantity of

ammunition.

In the days ahead the water situation

continued to weigh heavily on Eyre's mind. As water dwindled the aboriginal

boys showed Eyre how to obtain water from the roots of Eucalyptus

trees. Eyre was impressed to note that the quantity of water contained

in a good root would probably fill two thirds of a pint. His own boys,

as inexperienced as they were, even managed to obtain one third of

a pint in the space of 15 minutes.

By 29 March Eyre's expedition had consumed

their very last drop of water. The situation was now very grave and

required a desperate solution. Eyre's plan of action was carried out

the next morning when he observed that there was a heavy dew hanging

down from the grass and shrubs. With a sponge in hand Eyre dabbed

at the dew and squeezed water into a quart pot. The aboriginal boys

did likewise, gathering dew using a handful of grass instead of a

sponge. Altogether Eyre's party had gathered 2 quarts of water. In

the very best of British traditions Eyre's party then indulged in

the luxury of brewing up some tea in the remote Australian outback!

Eyre's Sandpatch and The Prospect of Starvation

Throughout the remainder of 29 March Eyre's party

plodded along until they reached some huge white sand drifts. In great

suspense members of the expedition frantically dug in the hope of

discovering water. Six feet down and seven days from the last wells,

Eyre's expedition had finally found another source of fresh water.

Today residents of the Nullarbor know the

area as Eyre's Sandpatch, a site located 50 kiometres southeast of

the present township of Cocklebiddy. As a site of historical significance

Eyre's Sandpatch is of considerable importance. In the past Eyre's

Sandpatch has been the site of a major repeater station for the telegraph

line linking the eastern states and Western Australia. The old telegraph

line was abandoned in 1927 however, and today the area is a major

Bird Observatory and site for a remote meteorological station

For 29 days Eyre based the expedition

at the "Sandpatch", hoping that his pack horses would regain some

of their lost strength. Attempts were also made to retrieve stores

that had been previously abandoned 47 miles to the east. Retrieving

these stores proved to be difficult, and much to to Eyre's regret,

one horse became blind and had to be abandoned, another perished from

sheer exhaustion.

By April the expedition's food supplies

were critically low and Eyre was forced to reduce meagre food rations

even further. Two plain meals of tea and damper per day proved insufficient

to sustain life however, and Eyre's party were forced to partially

live off the land - hunting for fish, sting rays and wallabies. Faced

with starvation Eyre's expedition even resorted to roasting bark from

the roots of young Eucalyptus trees. Imitating the local aborigines,

Eyre roasted the bark to a crisp, and then pounded it between two

rocks before chewing it. Eyre believed the roots were quite nutritious,

and according to his journal the roots ".. tasted rather sweet, somewhat

resembling the taste of malt."

By April 16 the food situation was as

desperate as ever, and Eyre ordered Baxter to butcher a horse that

was more dead than alive. For a few days horse meat provided the expedition

with its main source of food.

Seeds of Disunity

Throughout April seeds of disunity were

beginning to appear within the expedition. John Baxter, the loyal

overseer, was beginning to voice deep misgivings about continuing

the journey to King George's Sound - still over 600 miles away. For

Baxter, the expedition's best hope for survival lay in a swift retreat

to Fowlers Bay. Eyre clearly thought otherwise, believing that the

expedition had passed the point of no return.

The morale of the aboriginal boys was

no better, and on 22 April Eyre discovered that they had been pilfering

the expedition's meat rations. In response Eyre reduced the boy's

meat rations and there was a rebellion of sorts. Both Wylie and Joey

fled camp, probably believing that their best chance for survival

lay in striking out to the west on their own, and fending for themselves.

Events were to prove otherwise however,

and 5 days later Wylie and Joey returned to Eyre's Sandpatch in a

state of near starvation. Despite the poisoned atmosphere the boys

were welcomed back and they heartily ate an excellent stew - one made

from an eagle that Baxter had shot.

The Tragic Death of John Baxter

April 27 saw Eyre's expedition again heading

towards King George's sound. Eyre knew full well that the expedition

would need to make another desperate push through 150 miles of waterless

country. As the expedition headed west an abrupt line of cliffs met

their gaze. From naval charts Eyre knew these were the great cliffs

of the western escarpment, and they were just as threatening and imposing

as those he had seen hundreds of miles away to the east. To make further

progress Eyre's party resorted to walking along the immense clifftops,

passing through dwarf tea tree scrub broken by limestone outcrops.

On the evening of 29 April Eyre's expedition

camped for the night, hoping that a gale blowing from the southwest

would bring rain. Whilst Baxter and the boys were asleep, Eyre attended

to the packhorses which were grazing on patches of grass near camp.

At about 10-30 pm tragedy struck. As Eyre was returning to camp he

was startled to see a flash, one that was immediately followed by

the sound of a gunshot.

Near camp Eyre met an agitated Wylie who

cried out "Oh Massa, Oh Massa, come here." Upon reaching the campsite

Eyre was horror struck to see his loyal friend Baxter lying face down

covered in blood, in the last throes of death. Baxter never spoke

another word, and Eyre noted the 2 boys Yarry and Joey had fled, taking

with them 2 double barrelled shotguns. Baxter's death was definitely

a case of murder.

For Eyre, Baxter's death was a personal

tragedy and disaster of the greatest magnitude. The despair and anguish

Eyre felt is best described in his journal where he wrote:

| The frightful appalling truth now burst

upon me, that I was alone in the desert. He who had faithfully

served me for many years, who had followed my fortunes in adversity

and prosperity, who had accompanied me in all my wonderings,

and whose attachment to me had been his sole inducement to remain

with me in this last, and to him alas, fatal journey was no

more. For an instant, I was almost tempted to wish that it had

been my fate instead of his. The horrors of my situation glared

upon me in such startling reality, as for an instant to almost

paralyse my mind. At the dead hour of the night, in the wildest

and most inhospitable wastes of Australia, with the fierce wind

raging in unison with the scene of violence before me, I was

left with a single native, and who for aught I knew might be

in league with the other two, who were perhaps even now, lurking

about with the view to taking my life as they had done the overseer."

|

Baxter's Unusual "Burial" and Further Confrontations

By daybreak of 30 April Eyre had set to

work surveying the situation and making preparations for departure.

To Eyre's relief Joey and Yarry had left behind 40 pounds of flour,

some tea and sugar, and 4 gallons of water. To be sure these were

meagre rations, but they were all Eyre and Wylie could expect for

the next 600 miles. By 8 O'Clock all that remained was for Eyre and

Wylie to attend to Baxter's burial - if it could be called that.

For Eyre, this duty was more than ordinarily

painful given the vast sheets of unbroken limestone rock that extended

for miles in all directions. It was impossible to bury Baxter under

such circumstances and all that could be done was to wrap the body

in a blanket, leaving the body where it had fallen. Today the site

of Baxter's death is dignified with a memorial located 60 kilometres

south of Caiguna.

Baxter's

Cliffs

With their duty done, both Eyre and Wylie

marched to the west, departing the grisly murder scene. Eyre's intention

was to travel as quickly as possible in the hope of distancing themselves

from Joey and Yarry.

Events were to prove otherwise, and the

next morning Eyre observed both Joey and Yarry advancing towards him

with firearms at the ready. It was clear to Eyre that the 2 boys were

encouraging Wylie to accompany them. Wylie remained loyal to Eyre

however, and the other two boys were given some stark choices. Yarry

and Joey could either return to Fowlers Bay, or be shot if they continued

to threaten Eyre.

Fortunately there was no bloodshed, and

both Eyre and Wylie headed west. With the advantage of packhorses

Eyre and Wylie soon outpaced Yarry and Joey, and the two boys were

never seen again - by Europeans at any rate. In his journal Eyre expressed

the view that even Yarry and Joey's indigenous hunting skills would

not save them in this remote corner of the outback.

Spirits Rise and the Hope Inspired by a Trickle of Water

By May 1 both Eyre and Wylie had already

travelled for 5 days without discovering fresh water supplies. Hunger,

thirst and exhaustion continued to remain ever pressing problems for

man and beast alike. As the pair walked to the west spirits rose when

Eyre saw some stunted examples of Banksia plants - a species Eyre

well knew to be commonly found within the vicinity of King George's

Sound. Eyre also observed that after 148 miles from the last waterholes,

the never ending cliffs of the western Nullarbor were finally coming

to an end. Within a few miles of the cliffs terminating Eyre had discovered

another set of native wells. Although still 450 miles from King George's

Sound Eyre had good reason to believe that the last of the cruel waterless

stages had been traversed.

By May 8 Eyre was forced to butcher another

of his horses. Eyre's companion Wylie was ecstatic with delight, and

that night he roasted and ate over 20 pounds of meat and entrails.

For Wylie it was a veritable feast. Eyre was always astounded by Wylie's

appetite and was moved to note that under normal circumstances he

was quite capable of eating 9 pounds of meat per day.

For the next ten days Eyre and Wylie skirted

the coastline travelling southwest towards Point Malcolm and Cape

Arid. Just before Point Malcolm, Eyre was excited to note that the

rocky limestone country was changing and giving way to a rough grey

granite. Even better, some mountain ducks were seen aswell as a large

tree trunk found washed up upon the beach. Eyre was firmly convinced

the expedition's fate had taken a turn for the better.

Further proof came with the discovery

of a few drops of water trickling down a granite outcrop. For Eyre,

this was something of a miracle, and he was moved to write .. " ..

this was the only running water we had found since leaving Streaky

Bay, and though it hardly deserved the name, yet it imparted as much

hope, and almost as much satisfaction as if I had found a river."

Wylie Eats A Penguin

By 18-19 May both Eyre and Wylie were

reportedly suffering from a creeping apathy and torpor. Eyre perceived

the condition to be life threatening and the daily chores of life

proved to be a toil, especially digging for water twice a day. Unscheduled

rest stops were frequent and it was difficult maintaining the motivation

to continue. At times such as these, Eyre wrote, "... I could have

sat quietly and contentedly, and let the glass of life glide away

to its last sand."

For a few days Eyre and Wylie were forced

to rest near Point Malcolm. At Point Malcolm the pack horses found

good grazing, whilst Eyre and Wylie lived of the land - procuring

kangaroos, possums, crabs and fish for their daily sustenance. As

ever, Eyre remained fascinated by Wylie's appetite. On one occasion

Eyre noted that Wylie had scoffed down " a pound and a half of horse

flesh, some bread, then the entrails, paunch, liver, tail and hind

legs of a kangaroo, followed by a penguin found dead on the beach."

Eyre Departs Point Malcolm

On 26 May Eyre broke camp with the intention

of proceeding to Lucky Bay. Eyre left Point Malcolm in good spirits,

knowing full well that the naval explorer Matthew Flinders had discovered

abundant water supplies at Lucky Bay. For the very first time Eyre's

expedition had no need to dig for precious water.

Whilst the water may have been abundant,

food supplies continued to remain precarious however, with the expedition's

flour provisions almost exhausted. As a substitute for flour, Eyre

ground up and roasted the roots of flag reeds. In this form the Australian

native flag reed provided a staple food to both Eyre and Wylie.

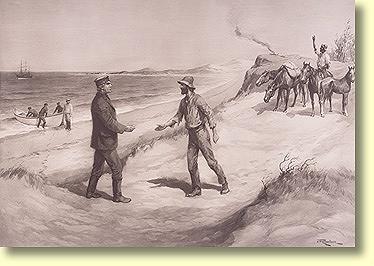

Rescued By a French Whaling Ship

Near Cape Arid Eyre trekked accross a

headland, traversing granite rises and fording a number of brackish

streams. By 2 June Eyre and Wylie had reached Lucky Bay - completely

unaware that what was about to happen would be beyond their wildest

dreams.

Hardly believing his eyes Eyre spotted

two small sail boats. Eyre and Wylie frantically pushed on attempting

to signal the sail boats. All their attempts failed, but there was

still good reason for hope as Eyre spotted the masts of a ship poking

above an island 6 miles away. The glorious sight of the ship so overwhelmed

Eyre and Wylie that they both skipped about with cries of joy at the

prospect of food.

Salvation was at hand, if only they could

attract the attention of those on board. Eyre then mounted his fastest

horse and galloped 6 miles to a clifftop, from where he could clearly

see a French Whaling vessel moored in the Bay. Eyre and Wylie quickly

made a large fire and successfully attracted the attention of some

French sailors who were cleaning ship's cables. Within minutes Eyre

was on board and enjoying the hospitality of Captain Rossiter, the

English Master of the French Barque "Mississippi"

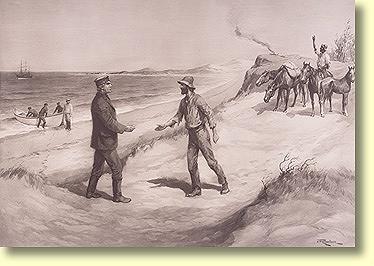

Eyre saved by Captain Rossiter

For 12 days Eyre and Wylie were treated

as privileged guests. In a dazed state Eyre could not help but thank

God " for the inexpressible relief afforded us when so much was needed

and so little expected." Eyre's fate had changed immeasurably. No

longer were he and Wylie subject to starvation, exposure to the elements,

and the intense cold of an Australian winter. Eyre now knew that with

replenished stores, and renewed physical vigour, the goal of King

George's Sound was now assured - even if it was still 300 miles away.

For Wylie, life on board the "Mississippi"

was no less gratifying. Biscuits were in abundance and at first the

French crew were horrified to see Wylie's unbridled appetite in action.

Eyre admired Wylie for making the most of the situation, and later

Wylie's eating habits became a source of amusement to all on board.

The Final Push to King George's Sound

By 14 June Eyre had decided the time was

right to push on to King George's Sound. Captain Rossiter again proved

himself to be a "Good Samaritan of the Sea". Captain Rossiter's generosity

knew no bounds, and Eyre's expedition departed with 40 pounds of flour,

6 pounds of biscuits, 12 pounds of rice, 20 pounds of pork, 2 bottles

of brandy, mountains of tea, sugar and butter, and to cap it all off,

6 bottles of very drinkable French wine. Wylie too was presented with

the fine gift of a pipe, and a large supply of tobacco - of which

he was apparently very fond.

With renewed vigour Eyre and Wylie commenced

their 300 mile trek to the west. Conditions were always difficult

and Eyre and Wylie battled their way through thick scrub interspersed

by stony ridges. For most of the next 10 days Eyre and Wylie had to

bear with constant drenching rain and bitterly cold weather. To add

to their miseries, occasional torrents of rain poured down, and for

many days the ground beneath their feet was covered by sheets of water

- sometimes several inches deep. The contrast with Eyre and Wylie's

experience of the Nullarbor was total. It was impossible to sleep

under such soaking conditions, and at night all that Eyre could do,

was to walk around in order to remain warm.

Travel conditions proved to be energy sapping

both for man and beast alike. For a number of days both Eyre and Wylie

were forced to routinely detour around flooded streams - and when

they weren't doing this, flooded rivers had to be forded. These misfortunes

added many unwanted days and miles to their journey.

By 30 June 1841 Eyre and Wiley were within

sight of the Stirling Ranges. Eyre knew that the destination of King

George's Sound was near at hand. It was only a matter of days at most,

and Eyre reported that Wylie too was very greatly cheered by the prospect

of reaching home. Apparently for the first time in the entire expedition

Wylie really did believe that he would live to see his kinsmen and

tribal lands again. For the next few days the scrub lands gradually

transformed into a finely wooded countryside, and Eyre noted the area

as being eminently suitable for grazing.

As the expedition approached King George's

Sound Wylie assumed the role of a guide. Signs of European settlement

were present, and both Eyre and Wylie were spurred on by the sight

of a horse's hoof marks - moreover, the tracks were only a few days

old. The very next day excitement levels were wracked up a further

notch when Wylie recognised a lake from his past travels.

Emotional Reunions

By 6 July Eyre and Wylie had reached King's

River - a few short miles from King George's Sound. One last obstacle

arose for Eyre and Wylie however, the river was just too high. Eyre

was unwilling to wait for the flood tide to recede and so he and Wylie

abandoned their horses and crossed the river on foot - holding only

the most precious of their possessions above their heads.

Eyre and Wylie then commenced the short

walk to King George's Sound. Along the track Wylie met with one of

his fellow countrymen who greeted him extremely warmly. Apparently

the natives of King George Sound had given up Wylie for dead. Wylie

was expected to have arrived 2 months earlier, and everyone had assumed

the worst and already mourned his loss.

A short time later Eyre, Wylie, and his

friend were standing on a hill, gazing down on the settlement of King

George's Sound. Eyre stood there in torrential rain and wept at the

sight. Wylie's friend then let loose with a series of wild joyous

cries announcing Wylie's unexpected return from the dead. The streets

of King George's Sound were abuzz and Wylie's people rushed to greet

him. Understandably there were many deeply emotional reunions, and

Eyre himself noted, even the strongest ties off affection could not

have produced a more emotional and melting scene.

Eyre and Wylie Attend to Unfinished Business

Eyre's epic journey accross the Great

Austrlaian Bight had now come to an abrupt end. A number of matters

required Eyre's urgent personal attention however, and during the

next week Eyre organized the recovery of his abandoned horses. Both

he and Wylie also presented eye witness accounts to legal authorities

regarding the tragic circumstances of Baxter's death. Surprisingly

Eyre's feelings to Yarry and Joey had now mellowed - believing that

under the same circumstances many Europeans would have behaved no

better.

Farewells and Honours

13 July 1841 saw Eyre bid a final farewell

to Wylie. Sadly, Eyre and Wylie were never to meet again, however

to the end of his days Eyre always held the highest esteem for Wylie.

A measure of this esteem is perhaps reflected in the fact that during

his appointment as the Lieutenant Governor of New Zealand, Eyre sent

Wylie the gift of a double barrelled shot gun. Wylie was apparently

very pleased to receive this gift. On another occasion. Eyre also

successfully interceded on Wylie's behalf when Western Australia's

Colonial government attempted to renege on its commitment to provide

Wylie with a monthly ration of flour and tobacco.

Upon returning to Adelaide Eyre was hailed

as a hero, and given his deep humanity and respect towards aboriginal

people, he was rewarded with a position as The Protector of Aborigines

at Moorundie Reach, near Blanchetown on the River Murray. The Royal

Geographic Society also recognized Edward John Eyre's feats in exploring

remote areas of Southern and Western Australia. During these epic

expeditions Eyre had proven there were few rich grazing lands in the

areas adjacent to the Nullarbor, and that for all intents and purposes,

there was no practical overland stock route between Adelaide and King

George's Sound - or Albany as it is now known. For these trials and

tribulations Eyre was justly rewarded with the Society's Gold Medal.

******

In

the spirit of reconciliation this site is dedicated to the memory

of Edward John Eyre and his companion Wylie.

"If

there is any road not travelled then that is the one I must take."

Edward John Eyre

|